Out the window, it’s snowing

Though it’s 27 degrees and sunny

The cottonwood has decided otherwise

Melancholy tufts of white

Disappear beyond the frame

“There is but one truly serious philosophical problem, and that is suicide.”

And we’ll all float on, okay

And we’ll all float on, okay

And we’ll all float on, okay

And we’ll all float on, anyway well

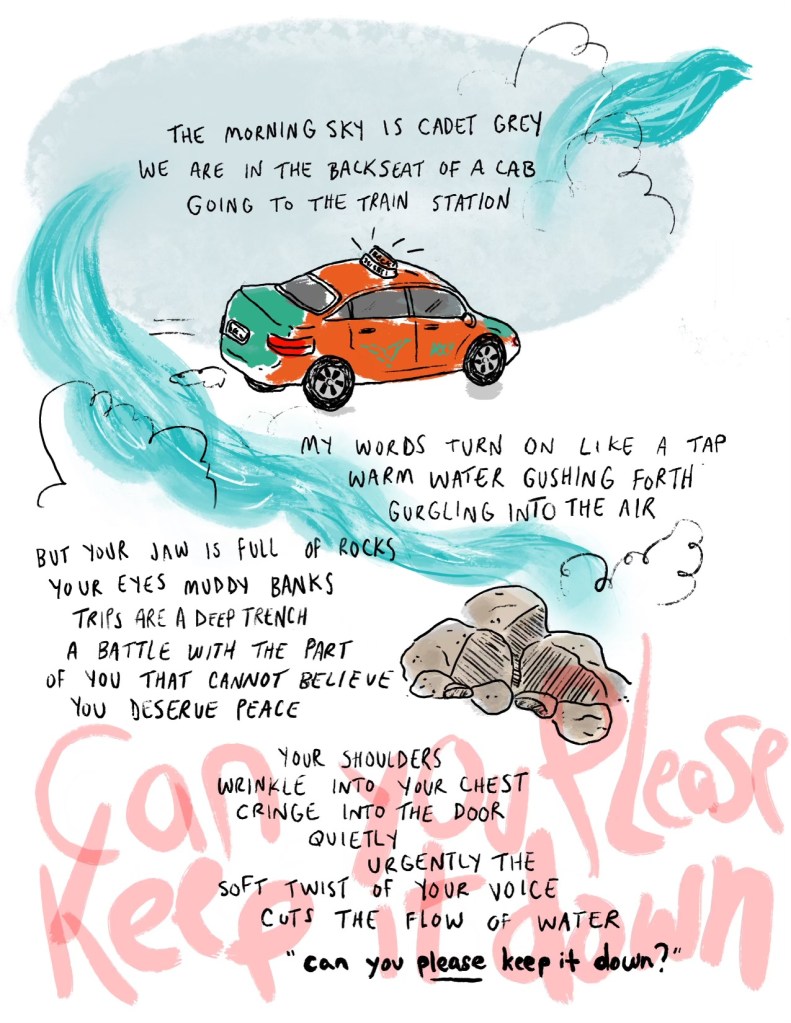

Out the window, it’s blurry

The trees, the sky, the electrical wires

Melt into a scream as the train proceeds

Black, red, blue, yellow, green

Yearning towards the next station

And the next

And the next

And the next

And we’ll all float on, okay

And we’ll all float on, okay

And we’ll all float on, okay

And we’ll all float on, alright

His eyes closed against the pressure of the sun, Derrick watches small vitreous fibers float through the hot pink sea inside his head. He has chosen the spot on the beach that’s as far away from people as possible. He opens his eyes and looks down at his legs, tinged a sickly yellow from the SPF 100 he’s just slathered on. He sits under an umbrella, arms crossed over his favorite Warhammer t-shirt. The old towel he’d taken from his parents’ linen closet has a large faded Tigger on it, the image punctured by white and orange pilling. Gently placing his hand on Tigger’s muted face, he begins to mumble under his breath in a monotone refrain:

The wonderful thing about tiggers / Is tiggers are wonderful things / Their tops are made out of rubber / Their bottoms are made out of springs / They’re bouncy, trouncy, flouncy, pouncy, fun, fun, fun, fun, fun / But the most wonderful thing about tiggers is I’m the only one / IIIII’m the only one!

He stops abruptly, staring at the reflection of the sun on the water. The ocean unsettles him; he’s watched just shy of 30 documentaries exploring the mysteries below. It’s an alien world full of ancient beasts, some we may never even know exist. And the violence of it! His mouth thins into a hard line. Nature is brutal, unforgiving, primal. And here are these idiots, splashing around like they don’t have a care in the world.

Picking up the worn spiral notebook resting beside him, he notes down that this is the third time he’s heard a mother scold her toddler for running too quickly – and done nothing to actively stop him. He also notes the bright neon green of her bathing suit, that she clearly hasn’t washed her hair (possibly in days), and that the toddler seems especially hyperactive. In the margins he scribbles, “Sugar? Bad mother? Childhood trauma? ADHD? Poverty?”

Though his weekly trips to the beach always put him in a bad mood, he considers them necessary expeditions, absolutely crucial to his research. He had lost his job at 1-2-3 Pizza! a year and a half ago, which only spurred on his belief that he is woefully misunderstood. Why was it so wrong to try and convince customers that vegan pizza is superior? Have they thought about how the horrific mixture of animal entrails once belonged to a living, breathing being? That the small circles of compressed flesh they were consuming had felt joy, pain, sadness, pleasure in the same way they had? Monsters, all of them – a pox. Which is why these anthropological outings are so important. Outside of his secondary research, he needs primary source material to prove the individualistic manifestations of the capitalist system.

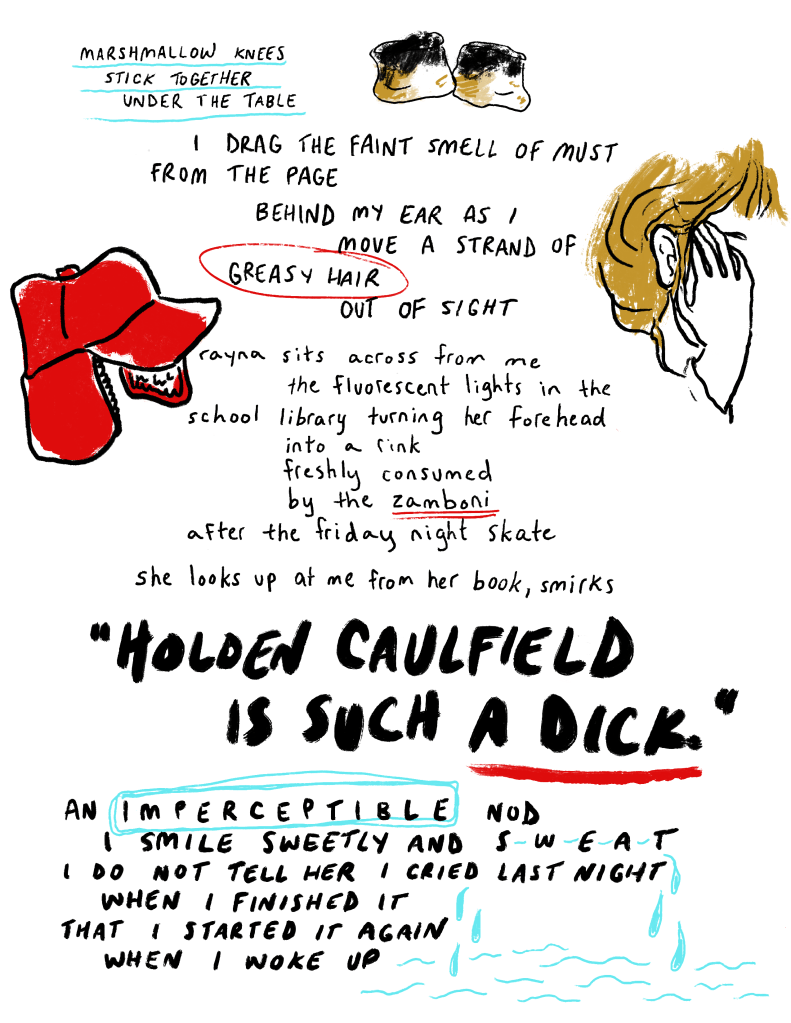

I am 16 and it is my first time

in the “Big Smoke”

You take me to a vintage store

and the retail clerk says

something about “your daughter”

Your teeth gleam and —

“She’s my granddaughter, actually”

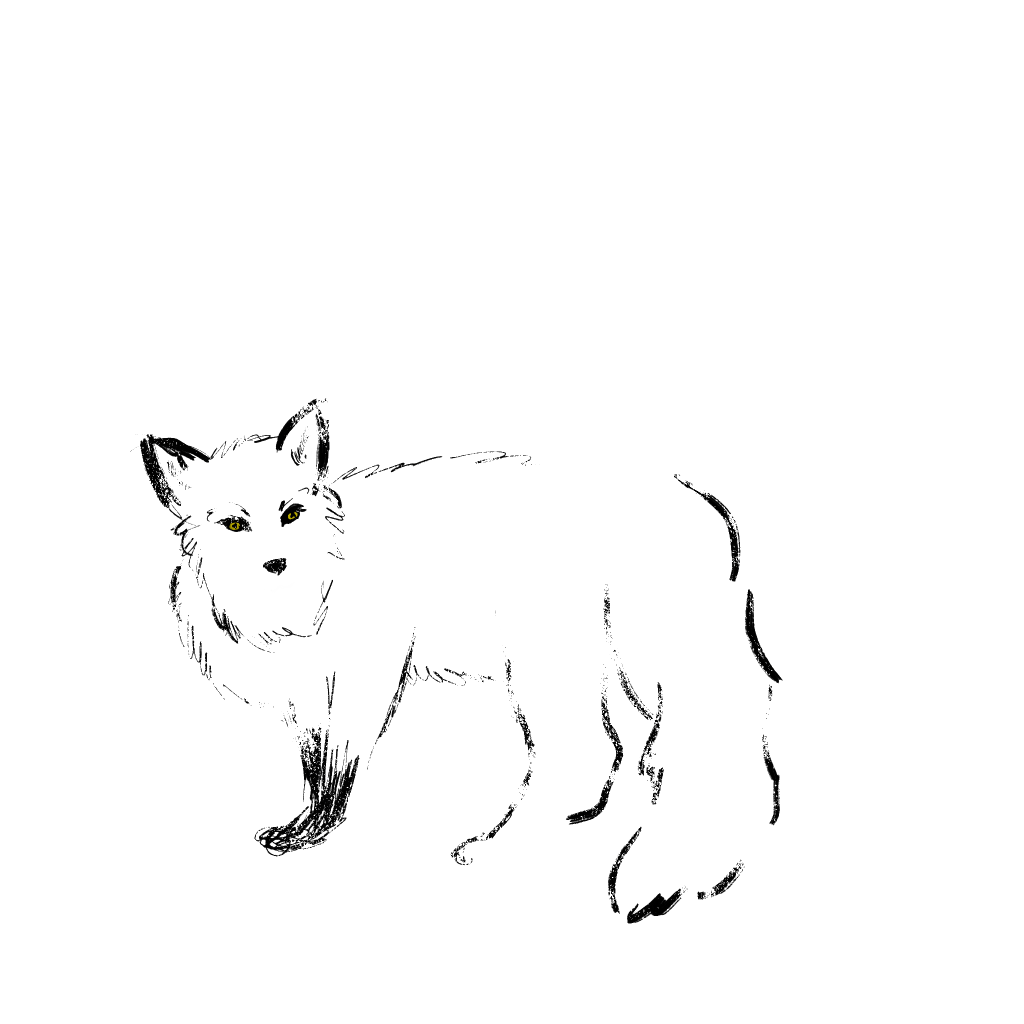

You were born a fox, now in your prime

you always know where the food is you

just wait for the right moment

to pounce and you

always know just when

You and B start to run

a bed and breakfast

out of your newly built home

When I visit, you make

pancakes and bacon

on the extra large grill

usually reserved for guests

We drink scotch at night you

grin and shake your head

because I like “that peaty stuff” you

give me advice I know I won’t

heed and we talk about the boat,

we eat, we lean close

Now is a time for rest,

you lay in your den

with your fox tail wrapped and

muted red about your face, eyes

harvest moons on dark water

B is supposed to be with you

but you arrive alone

We all know your memory

is going, you won’t admit

your reflexes are too

Driving one-handed, telling stories,

running red lights

I worry we might not make it

B just doesn’t have the heart

to tell you no

You turn back into a kit,

smaller now

all softness and quickly

tumbling, tumbling, tumbling

needs to be fed, protected, kept warm

7 am, I pace my empty apartment

Watching my phone from

across the room I see

“Mom” lash across the screen

trapped, refusing to accept

I let it ring but

I already know you’re gone

Old fox, you were so alive,

wise and mischievous to the last

But time is a hunter

and now your den collapses

Leaving nothing but dirt

The initial stages of grief are a time warp, a horrible pause. There are some feelings that defy language, some feelings that just are. Grief just is.

I’ve been rushing between projects, finding things to do that help me remember my limbs. No reading or brain work – tactile things. Painting. Cooking. Cleaning. Yoga. Death makes me want to forget my body, but I resist. I am resisting death, though it does not go away. We only resist death until we can’t anymore. We grow around our grief pockets, creating souls that look like a maze in Pac-Man. Filled with ghosts that will eat us if we let them.

In the early 1900s, a physician named Duncan MacDougall wanted to test whether the soul has weight. He conducted an experiment where he tried to measure the loss of mass the moment his test subjects died. The experiment was a flop. His sample size was too small, and the results weren’t consistent. One subject lost 21.3 grams. For some reason, even though other subjects also lost mass at time of death, when the results of the experiment were published, the 21 grams was what the media focused on. I’ve been told variations of this story over the years, and usually people can’t identify where they heard it.

Even though it’s horseshit, I can’t help but feel comforted by the concept. That must be why the myth lives on. What would it mean if humans have some kind of essence that animates our bodies? If it does exist, then my Gran has become unbound. A hypothesized 21.3 grams, into the aether.

Gran was incredible at sewing. She made all of my dresses when I was young, each with a matching hair tie or headband. There was almost always lace. Lots of lace. Our placemats for special occasions were all handmade by her. Mom still has the Christmas placemats. They’re thin, but vibrant even though they’re old now. They are edged in lace. They are beautiful.

When I was 11 years old, my friend Katie and I got really into sewing. We were especially drawn to accessories. Purses and scrunchies. I made a small rainbow purse that I wish I still had. Gran would send parcels from Ontario to Nova Scotia full of material scraps, all her leftover buttons, lace, ribbon. We looked forward to the haul every time. For a while, I became obsessed with buttons. Mom would take me to second hand stores on the weekends and I’d dig through their button bin, looking for treasure. I loved how the buttons came in sets, always tied together neatly and delicately with a fine piece of thread. Who tied them? Who sorted them, paired them up?

Gran used to visit us in the summer. Maybe she visited during other seasons, but for some reason I associate her with summer. Much like my mother, Gran loved the beach. I’m not sure if she passed that on to Mom, but in that way they are the same. In most other ways they are different, but they both love the beach. I love watching my mother at the beach. It’s like seeing an astronaut take off their suit. All monotony and care slips away in the presence of the ocean. A giant beating heart that reminds us we still have one. Sometimes Mom sits on her towel in total silence, eyes closed, a small smile on her lips. She doesn’t usually bring a blanket, just a towel. A towel is enough. I think my beach Mom is Mom as a little girl. Quiet, introspective, introverted, reflexive, sensitive, gentle. My Gran was the opposite of these things.

Gran wasn’t very good at using words to express her feelings. It’s not like she never said “I love you” – she did. But there was never a “because” attached to it. She did not love by noticing. But she never missed birthdays, and always sent gifts and cards. When I was 13, I got really into tracksuits and brand names. My family didn’t have a lot of money, so Gran would get me all the Nike gear I wanted. She used to call and ask for details about my life that even I thought were boring. It was in her wanting to know that her love lived.

Many years ago, Gran moved from her cottage by a lake to a long term care home. Her mobility declined and her body became frail. When she lived at the cottage, she would swim almost daily if the weather allowed. She had a dog that she loved. My Aunt Ginny took the dog, and she took on the responsibility of caring for Gran. Ginny is a nurse. She is retired now but, like everyone on my mother’s side of the family, she never stops moving. The Wilkins are all like this; there is almost too much electricity in their bodies. You can hear it crackling sometimes. I wonder how Ginny will rewire her circuit board now that Gran is gone.

Gran was a Smith first, not a Wilkins, and her energy left gradually but consistently. She spent the last decades of her life in the home. When I’d visit, I’d ask if she was taking part in activities, meeting new friends. Though she’d go to church services sometimes (for the music, she’d say), she preferred to stay in her room. As time went on her physical ailments prevented her from extended social interaction. If I was late for a visit, she’d get angry and mean with me. She started having more falls, ending up in the hospital. I would visit her there. Sometimes I would play Frank Sinatra for her on my phone, she’d ask about my job even though she didn’t understand what I do. Sometimes, when she was confused by drugs and trauma, she would yell at me. After a while, I stopped visiting. That is a ghost in my maze, now.

My mother once said that death is about those left behind. We are left with our regrets, our grief, our loss, our memories – good and bad. No person goes through life without hurting others, or being hurt. Pain is inevitable. Love is not; love is a choice. And love can sustain us, even through grief.